RELIEF Mass Displacement Public Services Middle East

Dr Ala'a Shehabi

Against the backdrop of MACAM's 2nd Biennale of Contemporary Art on the theme of Universal Data, which inspires visitors to interrogate our digital lives, the RELIEF Centre's Data Manager, Ala'a Shehabi, convened members of the small but growing Beirut data community in a safe space to discuss growing ethical anxieties around the increasing emphasis on Open Data. This included artists, media practitioners, data scientists, and rights activists eager to discuss their own data collection and publishing practices across various data initiatives. Meetings such as this are important towards building a data ethics community, a space to interrogate practices and their consequences, and support and solidarity for each other.

We asked; What data should be 'open'? Who is it 'open' for? What known risks surrounding openness must be take into consideration, and what known unknowns should we prepare for?

Within our critical data studies community, people working on the following social initiatives attended the first meet-up:

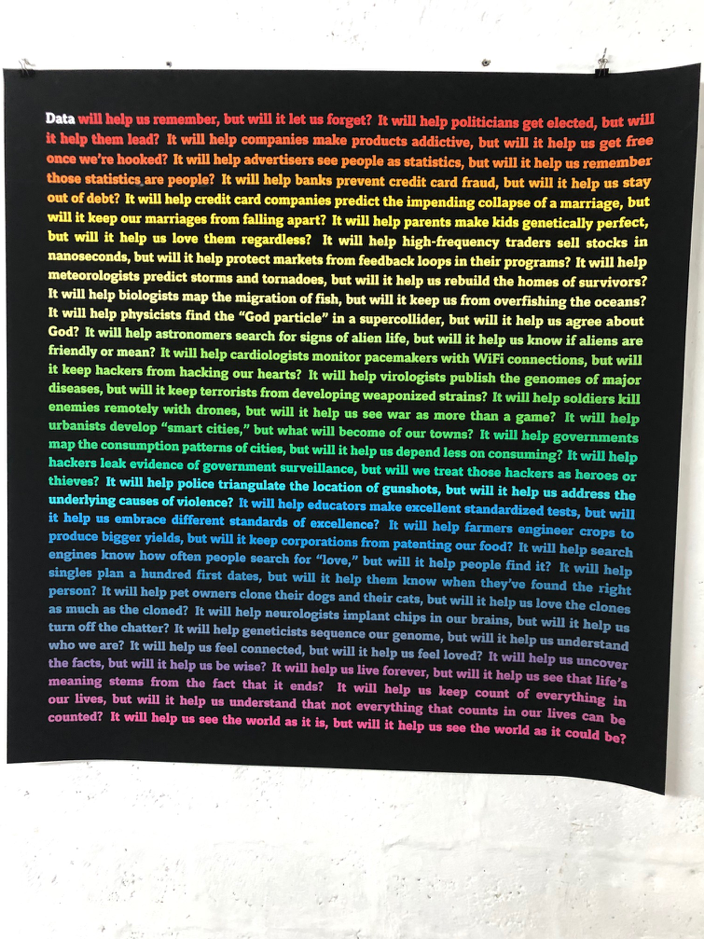

Data Will Help Us

To begin the workshop, participants spent an hour and a half exploring the data exhibition. This served to open hearts and minds to a continuous conversation lasting four hours continuously based on trust, familiarity and common interest in each others' work.

Questions around data and its use were expressed in Jonathan Harris' installation at the Biennale, Data Will Help Us, a manifesto that invites us to question data: "It will help us keep count of everything in our lives, but will it help us understand that not everything that counts in our lives can be counted? It will help us see the world as it is, but will it help us see the world as it could be?" This art installation invites us to think not just about data but what data can do. In this vein, we begin to question our own roles and responsibilities as data stewards working under the imperative that data is made necessarily 'open', that this openness leads to positive social impact in a linear correlation between knowledge production/accumulation and social policy change. This applies to 'digitalisation' across different sectors: from smart cities, to e-governments, and the mass digitisation of our physical and analog archives.

In addition, there are now a flurry of Western Open Data initiatives that are navigating the new politics of mass digitisation through privacy, regulatory and technical dimensions. In order to grasp the stakes of open data, we need to approach open data not purely as a technical issue or consequences to date are not yet fully understood.

Data in the Middle East

In the Middle East, there are few examples of large open data sets, and almost non-existent open government data initiatives. According to the Open Data Barometer, "There is not one truly open dataset in the region, out of the 180 datasets [.] analysed in [their] study." Data registers hide in their obscurity and data is heavily curated when published. Many of the states in the Middle East also deploy advanced digital surveillance and censorship tools.

Researchers from universities, the media, international NGOs and civil society groups who carry out data collection in the region are under increasing pressure to make this limited research data 'open'. The pursuit of open data promises us more original scholarship and better funding opportunities, and seems like an inherent radical endeavour in the face of restrictions on academic, media and civic freedoms. It also promises new ways of understanding, viewing and structuring knowledge, new forms of value creation and extraction, and new infrastructures of control.

A Narrative of Caution

At the workshop, participants expressed the following interests:

A narrative of caution emerged from the conversation. One participant pointed to the importance of responding collectively; "the important capitalist principle of efficiency is that we share data so we can work less. We want to see how our work intersects, and we want to engage on a higher philosophical level to develop a field of critical data studies from the Global South. Everyone here is involved in data politics in some way or another, whether we like it or not. We want to create a community where we discuss these things."

Image: Participants at the Ethics of Open Data workshop. (c) Ala'a Shehabi

Data storytelling

Several participants agreed with the point that "Data is data, data is not a narrative or a story. Access to primary source material is not finding a solution." This echoes Jonathan Harris' manifesto about what data can do, not what data is. A participant from an art background stated "Making data available is not what is interesting, telling stories is interesting...'You have the data, you have the answer" - no, this is about how it is interpreted for good or for bad. Institutions who don't open up, because they fear about what happens when it opens up is the key to understanding the resistance to opening up closed data. There are artists who photoshop and produce fake artwork, how are we going to authenticate artwork images? The question of open access, opening up archives allows people to manipulate, and in the extreme, fabricate. We would be supporting these different possibilities. The question therefore is what are the fears? For example, a private gallery in X country containing photos of families, histories. This letter may make someone look bad therefore we do not publish it. Or a woman in her 30s wearing a miniskirt and now she is a Hajjeh (a Hajj pilgrim) - we produce a history that doesn't show these histories, we may censor as a way of protecting."

Open Data

Another participant delved into the technicalities of some of the data initiatives who thought their initiatives were 'open', to comment "Open Data is not just about open source software, it is also open licensing and being able to download data."

As participants described their work, one common question emerged around data use, and how data can be effectively used for advocacy and social change. Specific comments on this were as follows:

On data ownership and access

Who 'owns' data? As data stewards we may need to retain proprietary ownership of data until we think through ethical risks and potential harm. How do we carry out due diligence and digital risk assessments? In practice, it is really difficult to decide what to keep private and what to make public. On the question of ownership, one participant who works for an NGO felt, "as an outsider, it is really difficult getting access to data produced by universities." Sometimes NGOs and activists would like to delve deeper into research data to help their campaigns. On the other hand, researchers with large datasets "Fear that data will get exploited by those with resources to analyse and manipulate data to use against target vulnerable communities." Another researcher who uses citizen scientists described a project where the "community controls what is open through a collaborative science and development network - contextualising openness."

Finally, "[u]nderstanding that data is part of a market, understanding profit motives even when innocuous seeming data, the combination, layering, augmentation of data is what makes it powerful."

Next steps

Many felt the conversations were unfinished, "when is the next event?" More meetings are planned around the Breat & Net conference in November. Specifically, a session on how we build a data threat model that comes with different kinds of open data projects. On the side, a sub-group of participants agreed for the need for some academic projects to collaborate on a data sharing sharing initiative to co-develop protocols around:

In terms of how to take the conversation forward, one participant suggested building an online forum. These ideas will be taken forward in the next session.

Fatemeh Sadeghi

30 May 2024 Feminists in the Global South have stepped out of the conventional territories of ‘women’s matters’ into more fund...