Professor Jacqueline McGlade

5 November 2021

Global challenges like climate change, land and ecosystem degradation, in addition to a growing, and highly urbanised, population call for new ways of producing and consuming within the planetary boundaries. The need to achieve sustainability while ensuring the prosperity and wellbeing of people constitutes a strong incentive to rethink our land, food and health systems, transform our industries and reimagine our cities.

The circular bioeconomy - the oldest business model in the world

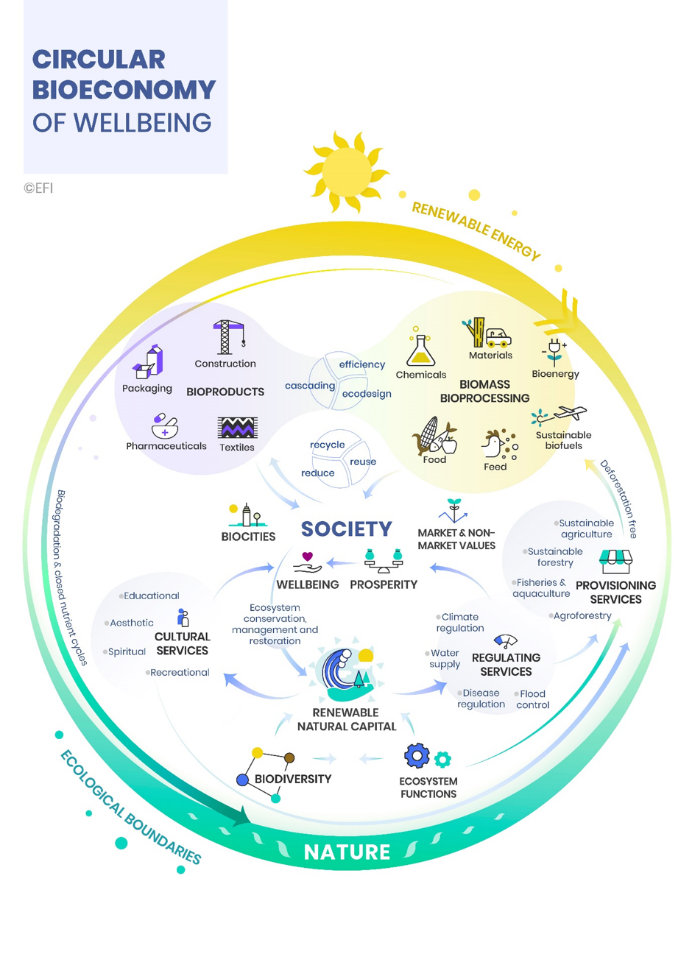

The circular bioeconomy draws on nature-based solutions to our everyday needs. It is about expanding the range of innovative products using agro-forestry-marine processes, opening up consumer markets with biobased solutions to create local industries and improve livelihoods everywhere. It relies on healthy, biodiverse and resilient ecosystems and aims at providing sustainable wellbeing through the provision of ecosystem services and the sustainable management of biological resources such as plants, animals, micro-organisms and derived biomass, including organic waste and its circular transformation in food, feed, energy and biomaterials.

A growing number of the world’s top CEOs, investors, political leaders and researchers consider the circular bioeconomy to be a critical element to addressing climate change and the challenges it presents. The circular bioeconomy is the oldest business model in the world. Nothing wasted, everything used and reused, with Nature as the powerhouse. It has the potential to solve the multiple challenges of encouraging local investment, generating prosperity by creating decent jobs and improving health, education and food security whilst protecting ecosystem services such as clean water, biodiversity and cultural heritage.

So how does it work and how quickly can it happen?

First, we must change the ways in which we use our forests. They can be much more than a source of certified timber and carbon sequestration. They are also a store-cupboard and reservoir of raw resources and services for a vast array of new and innovative construction, energy, packaging and textile products. Timber companies, formerly tied to producing just timber, pulp and paper, can now produce renewable and sustainable biofuels to help replace fossil fuel raw materials and reduce carbon emissions, packaging and self-adhesive materials, biocomposites and high-performance products for construction, revolutionary fillers for lightweight electrical insulation, different kinds of bioplastics, nanofibrilar cellulose hydrogel for 3D cell culturing to support human cells and tissues implants a vast array of textiles.

Second, there need to be improvements in agriculture and fisheries and support for the uptake of agroecology. This can help restore and maintain soil health, increase yields while reducing input costs and levels of pollution, produce more nutritious foods and supply the feeder stocks organic waste for the industrial production of bioplastics and lubricants. In the same way, a more integrated value chain approach to fisheries can help create to new local industries, such as using the waste from fish processing to make bioplastics and other forms of packaging.

Circular bioeconomy crucial to achieve the Paris climate pledges

Climate change, land-use change, food production, material use and human health are all interconnected. This means that human interventions influenced by economic, social and political factors can cause amplifying feedbacks (positive or negative) among them. In a warming world, where greenhouse gas emissions need to be reduced and carbon stored, at the same time as ensuring everyone’s needs for food, housing, clothing and energy, it makes social and business sense to invest in a circular bioeconomy. Unlocking the potential of the circular bioeconomy to decarbonise the global economy while enhancing natural capital and ensuring greater social equality requires a deeply transformative set of policies that link land and marine stewardship to well-articulated biobased value chains, innovative product design and regulations and clear consumer advice.

Circle Economy (a group supported by UN Environment and the Global Environment Facility) calculates that 62% of global greenhouse gas emissions are released during the extraction, processing and manufacturing of goods. Only 38% are emitted in the delivery and use of products and services. Yet global use of materials has more than tripled since 1970 according to the UN International Resource Panel.

A circular bioeconomy relying on and providing renewable energy and low carbon biobased solutions while enhancing natural sinks is necessary to build a carbon neutral future in line with the climate objectives of the Paris Agreement (see below). Planting millions of trees, regenerating the health of our land, establishing innovative biobased product technologies – all core elements of the circular bioeconomy - will not only help achieve net zero-carbon emissions more quickly, but ensure the livelihoods of millions and local community prosperity in the face of climate change. Transforming the land sector (agriculture, forestry, wetlands, bioenergy) towards more sustainable practices could contribute an estimated 30% of the global mitigation needed in 2050 to deliver on the 1.5°C target (see below). To achieve this, scaling up sustainable agriculture practices, marine management systems and climate smart forestry measures are needed to meet the demand for food while providing key regulating ecosystem services and sustainable feedstocks for producing biobased products and bioenergy.

26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26)

The UK will host the 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) in Glasgow on 31 October – 12 November 2021 to bring together world leaders to commit to urgent global climate action. COP stands for the 'conference of the parties' and is the main decision-making body of the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Under the Paris Agreement (in 2015 COP21 took place in Paris) countries committed to bring forward national plans setting out how much they would reduce their emissions – known as Nationally Determined Contributions, or ‘NDCs’. The aim of these pledges is to limit global temperature rise to well below 2 degrees and to keep warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius. Countries agreed they would come back with an updated plan every five years.

The Paris commitments did not come close to limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees. Cop26 has now a unique urgency and world leaders will be under pressure to step up their efforts to deliver action plans for achieving the Paris Agreement goals set at COP21.

Professor Jacqueline McGlade is Professor of Natural Prosperity, Sustainable Development and Knowledge Systems at the Institute for Global Prosperity (IGP) at UCL and lead scientist for PROCOL Kenya.

Her current research interests include impacts of climate change on human and ecosystem health and the development of the circular bioeconomy with a focus on agri-forestry systems in Africa, Small Island Developing States and the UK.

Professor McGlade has previous experience at international climate negotiations and attends COP26 as part of UCL’s team of experts. She will discuss the Circular Bioeconomy as well as agriculture and land use, carbon markets, climate adaptation around water scarcity and plastics.

Twitter: @JacquieMcGlade

Photo by Geran de Klerk on Unsplash

Fatemeh Sadeghi

30 May 2024 Feminists in the Global South have stepped out of the conventional territories of ‘women’s matters’ into more fund...