RELIEF Prosperity Index Middle East

Soheila Shourbaji

Maps, Anxieties and Reconceptions: An Ethnography of Citizen Social Science in Hamra’s Prosperity Index Projec

“What’s this street called?”

“Bliss.”

“What?”

“Bliss. Bliss.”

“What does that mean?”

“It’s where university students eat.”

Bliss street is the American University of Beirut’s frontier with Hamra. It is named after the institution’s founder, Daniel Bliss, and, indeed, it is where students eat. I heard the above conversation as I passed through the street on a Tuesday morning on my way to the Neighborhood Initiative’s office for my internship with RELIEF. The conversation made me think about possibilities of understanding urban life and navigation, which are central to the way in which people experience and conceptualize the meaning of prosperity in their lives.

RELIEF’s work on prosperity is grounded in citizen social science in order to produce community-based research findings that are owned by, and intended for the use of, local residents and organizations. The interaction between citizen scientists and the residents of Hamra was a condensed and strenuous node of the project that I wanted to explore in detail. This was an opportunity to observe people’s perceptions, bodies of knowledge and articulations of experience through close work with the citizen scientists and participation in interviews and surveys.

Hamra has long been romanticized as one of Lebanon’s most “sect-neutral” and harmonious neighborhoods. In this context, the RELIEF Centre’s research set out to understand how prosperity is conceived locally and how it can be measured through a set of context-specific indicators. But in addition to this, my work with RELIEF revealed that prosperity is also about a series of practices – the ways in which boundaries and identities are contested, redrawn and diffused on an everyday bases in a place such as Hamra which is experienced as fast paced by some and slow paced by others for all kinds of socioeconomic reasons. The ethnographic observation I carried aimed to understand citizen science as it became a part of the community, and a tool for allowing people to express verbally, but also emotionally and physically, what prosperity means for them.

I wanted to find out how people knew what they did and how they talked about it. I wanted to understand the local epistemology of everyday life from referants (in an unironic postmodern sense), memories and explanations. I was interested in matching academic conceptions used in university discourse to local understandings and lived realities. I was also greatly interested in the materiality of habitat through the stories people told about objects, their affects and their genealogies. The dynamic between citizen scientists and the residents of Hamra entailed many fronts that I wanted to identify through the exchanges outside the survey, the level of formality and the perceived threats and alliances. This was relevant to the question of knowledge production through citizen social science in general and the experimental play-out of boundaries and identities in Hamra. Finally, I also wanted to leave space for things to catch my attention and make me ask non-self-confirming questions – questions about how what I saw and did not see related to people’s visions and aspirations for a prosperous neighbourhood and a good life.

In retrospect, I realized that research interviews have limits to how informative they can be because they are for the most part artificial encounters that don’t happen spontaneously in everyday life. But at the same time there is also an element of “real life” that one experiences in the course of an interview. Interviewees would offer us coffee like the coffee pot depicted on the posters promoting our project in Hamra. The interview process has a content of what is said and an embodiment or enactment of emotions, both of which reveal an epistemology that should be appraised for its usability. The latter, in my view, is part of uncovering how inequalities are experienced, created and perpetuated, and how aspirations and hopes animate people’s physical and social interactions.

What I did not anticipate at the outset of my work with RELIEF, but learned throughout my research, was that the emotional space of the interview is of immense significance. Reflections, anxieties and exhilarations distinguished one interview from another. Talking about both dire and good life conditions played out within more or less the same form of encounter between the interviewer and interviewee. Boundaries differentially surfaced at some points and diminished at others, thus bringing whole arrays of emotion for everyone involved.

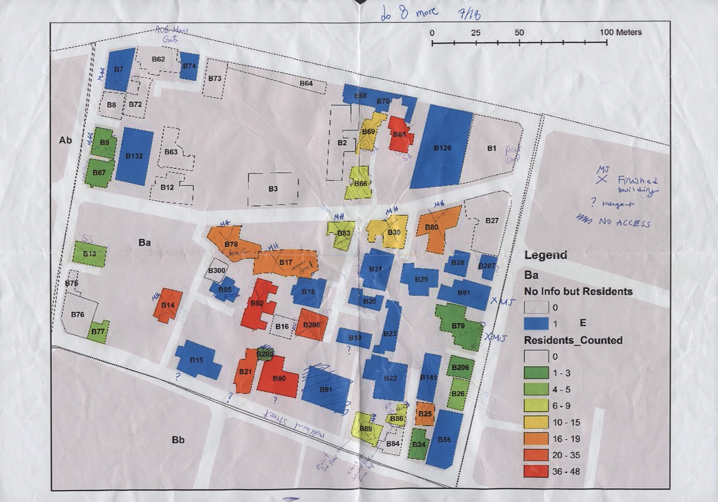

Working as part of the Prosperity Index research team has changed the way I see and experience Hamra. The map I received for the zone in which I was interviewing household heads became layered with street names, landmarks, notes and codes the same way that my mental map of Hamra got imprinted with stories, nuances and questions to answer in the future.

Soheila Shourbaji is a student at the American University of Beirut venturing in biology and anthropology. She is interested in intersectional feminism, creative research methods and infrastructure in the Middle East.

RELIEF is running a survey interviewing people from many different households in Hamra. RELIEF researchers will be asking Hamra residents about their quality of life and their neighbourhood. Help us re-think what prosperity means and develop new idea for governance and local interventions.

Top image credit: Samer Daboul from Pexels

Fatemeh Sadeghi

30 May 2024 Feminists in the Global South have stepped out of the conventional territories of ‘women’s matters’ into more fund...