Hannah Sender & Joana Dabaj

Lockdown is beginning to lift in Lebanon, but COVID-19 cases continue to rise and to exacerbate the terrible economic conditions that threaten people’s livelihoods and lives. We are not certain when we will be able to meet the people we have gotten to know and work with.

When I first visited the Beqaa Valley in 2016, I was accompanying a team of architects called CatalyticAction, who were building a school for children and teenagers living in an informal tented settlement. CatalyticAction co-design their buildings and playgrounds with the young people who will use the places they create. We have worked together ever since, researching the lives and aspirations of young people who live in the Beqaa Valley.

We are now thinking about how to continue our work, whilst ensuring the safety of the young people we work with.

There’s a lot that can be done online to facilitate valuable research and learning experiences. But before we rush into doing research online, we are reflecting back on our previous work, and asking ourselves what has worked well, and why. We want to recognise what young people value when they do research with us: things like creativity, interaction with friends, peers and adults, and being out in the world. We also want to recognise the barriers young people face in doing research, and participating in it: things like access to reliable internet, and safe areas to meet.

We decided to revisit a project we ran together in 2019 called ‘Adolescent Lives’, in partnership with UCL Global Health, University of Balamand, the American University of Beirut, the Lebanese Union for People with Physical Disabilities and Multi-Aid Programmes. You can read more about the project here: https://seriouslydifferent.org/igp-stories/blog-adolescent-lives-reviewing-our-findings-and-looking-to-the-future

Researchers of adolescence have used PhotoVoice as a method for working in collaboration with young people, particularly for projects about young people’s physical and social environments. It can be an accessible method, which gives young people the power to show the world they live in and things they care about, and makes this a starting point for conversations with researchers. In this way, young people instigate and drive the conversation in the direction they choose.

As part of our project, we conducted a series of PhotoVoice sessions with 30 boys and girls, coming from the different communities of Bar Elias, and with different cognitive and physical abilities. We used PhotoVoice to explore people’s environments, and reflect collectively on them. At the end of the project, the young people curated a selection of photographs and invited friends, family and others living and working in the area to an exhibition of their work. The team also exhibited their photographs at UCL as part of the 2019 It’s All Academic Festival.

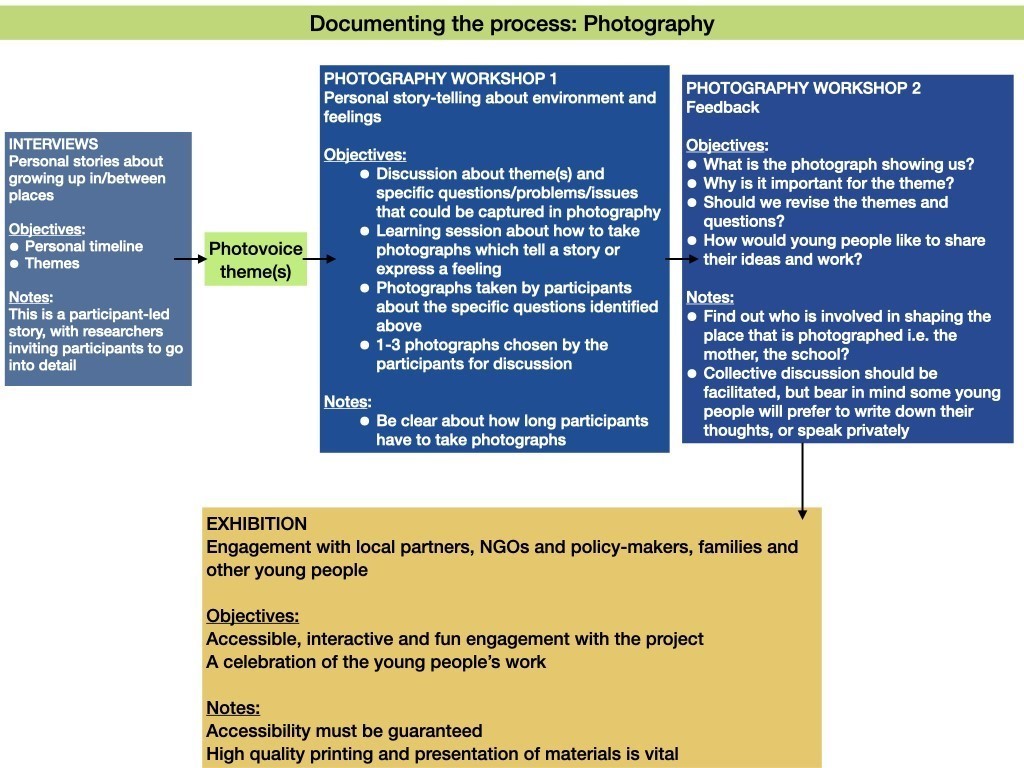

You can see our process here:

The initial photography workshops provided safe and encouraging spaces for young people to discuss the power of photography to tell stories about mental health and wellbeing, and to learn a new skill, test it out and then use it around their neighbourhoods and in their homes. We briefed the photographers about what we were interested in: photographs of important people and places in Bar Elias, which affect their mental health. We had talked at length with each photographer about mental health in earlier interviews, so the subject was not new to them.

The young photographers were able to direct the conversation about mental health in a positive direction, by choosing to highlight the places and people that support their mental health.

Osama was one of several young people to photograph nature in the area, which they enjoyed alone as a place of respite and with friends and family. He describes happy memories of visiting a specific part of the Litani River. Although the River has been repeatedly discussed in a negative light by adults living in the area (it is heavily polluted and deemed dangerous), young people continued to value the river as a place to pass the time with family and friends, and to recollect one’s thoughts.

Photograph by Osama

During the training session, the young photographers showed an interest in using photographs of people in dramatic poses, and using colour, to communicate an emotion or social norm. They appreciated that photography could be used creatively, as a metaphor for something which cannot be photographed directly.

Some of the young photographers shared their photographs with one another as well as the research team, as a way of communicating their emotional experiences. Take a look at Mariam’s photograph of a tree, which she describes as a metaphor for her ability to grow, to have a sturdy base (the trunk) and to have choices about her future (the branches). This photograph was eventually chosen to be exhibited, because it captured feelings of resilience, hope and concern about the future that many young people described during interviews.

Photograph by Mariam

Whilst most young people focused on their everyday lives in Bar Elias, a young Syrian man chose to exhibit a photograph which elicited memories of Syria. He photographed a tree which grows outside his home on the outskirts of Bar Elias. He described how fruit and plants grew in and around the garden which reminded him of his home town in Syria. His mother cooks with the plants – turning that visual memory into a memory of taste and smell. The tree and the plants growing around it gave him a sense of belonging and family in Lebanon, by connecting him to his childhood memories.

Photograph by Amin

Whilst their photographs varied in terms of their subject matter, there were some commonalities which tied their work together. It seemed that PhotoVoice gave young people an opportunity to celebrate the people, places and things which make them resilient in the face of challenges, and to complicate narratives imposed on them by experts, politicians and even neighbours. Whilst young people did share their frustrations, challenges and sadness with us during interviews we held prior to the photography workshops, they took pleasure in PhotoVoice as a way of showing another side to themselves: not only vulnerable and at risk, or even ‘troublemakers’, but embedded within their communities and neighbourhoods, and supportive of others around them.

The Photovoice exercise also gave young people an opportunity to meet new people from different communities, and to develop their support networks. When I returned to Bar Elias in 2020, I met with a few of the young people we’d worked with. Amin and his brother had begun attending classes at one of the NGOs we were working with and had made good friends with two of the other participants in the workshop. They are now learning to read and write with the LUPD, determined to make up for the loss of education they experienced when they were first displaced from Syria.

Thanks to mobile technologies, and the wide use of WhatsApp in Lebanon, it is possible for us to continue working on PhotoVoice projects with young people. They can interact in a WhatsApp group, and discuss the photographs. However, we know from experience that many young people’s mobile phone use is limited, and often scrutinised by family members. We hope that the relationships we have been able to develop over the years with young people and their families will enable young people to work with us virtually while our mobilities continue to be restricted. Whilst we embrace new ways of working with young people, our reflections have made us place even more value the relationships which we were able to form in person.

Image credit: Julius Drost on Unsplash

Fatemeh Sadeghi

30 May 2024 Feminists in the Global South have stepped out of the conventional territories of ‘women’s matters’ into more fund...